The Finns were favorably disposed towards the emperor for many reasons. Mainly two political groups existed in Finland: the Fennomans and the Liberals. The emperor’s aim was to reduce the Finnish contacts with Sweden and to bind the country closer to Russia. The Finnish railroad was begun in the late 1850s. The Fennoman Johan Vilhelm Snellman was professor in philosophy at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki and deputy assistant. The official status of the Finnish language and culture were promoted on his initiative. The emperor signed the proposition in 1863 and thus the Finnish language received official status in Finland. Industrialization began in the 1860s, and the railroad tied Helsinki and St. Petersburg together in 1870. At the same time Finland experienced economic growth. Finland got a currency of its own, the markka and penni that remained until 2002.

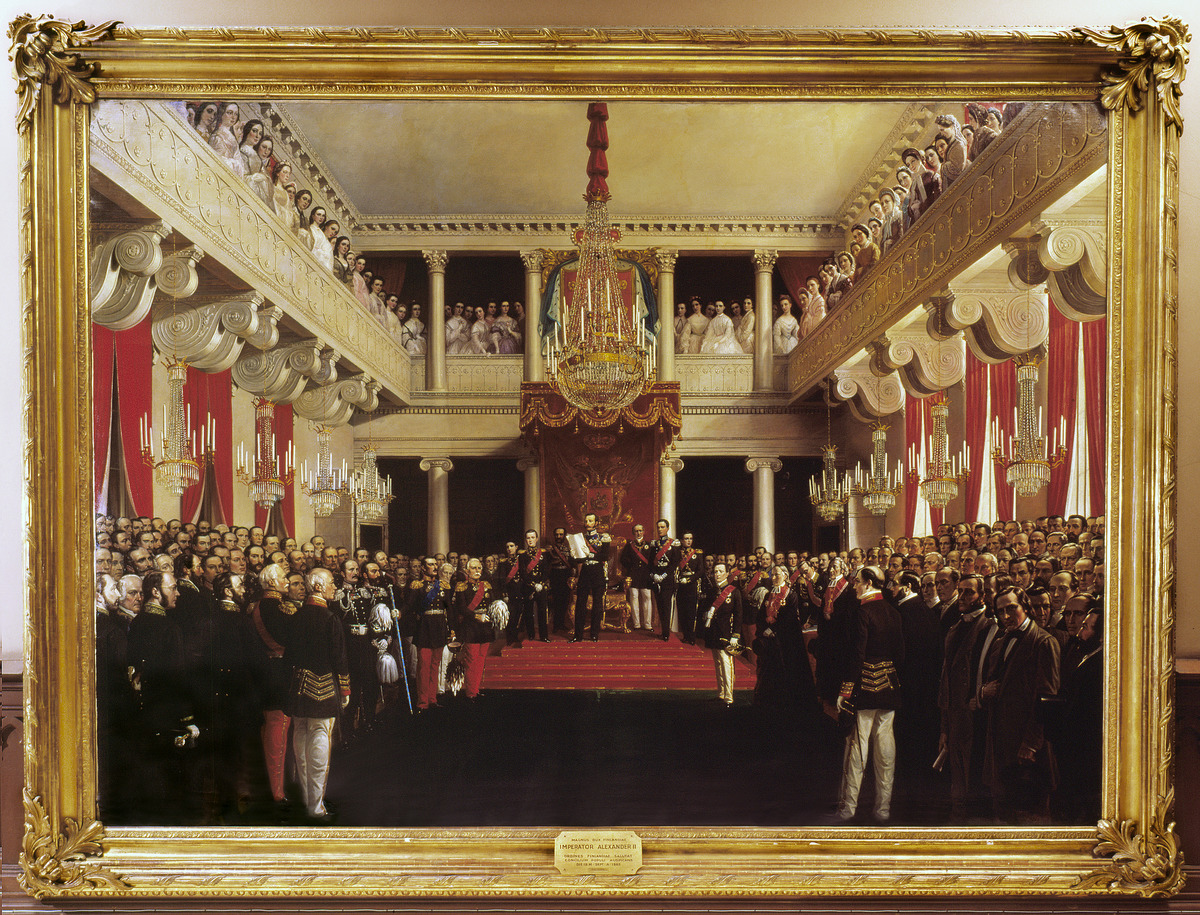

The liberal emperor Alexander II opened the assembly of the land in Helsinki in 1863. Major political changes could thus be made, resulting in the development of Finnish society and the Finnish culture. Photo: National Board of Antiquities (finna.fi).

The emperor’s political efforts were a success. He made liberal, enlightened reforms, freeing 23 million people from serfdom in Russia in 1861, and reforming the Russian legal system. A revolt still broke out in Poland. Count Fredrik Wilhelm Rembert Berg rushed there and assumed military control. During this reign Russian territory was enlarged in Asia. Russia made great victories in the war against the Ottoman empire in 1877 and 1878. Despite these advances, political terror in Russia grew. A Polish terrorist assassinated the emperor in broad daylight. The Church of the Resurrection stands on this spot today in St. Petersburg. The emperor was wounded and brought to the Winter Palace where he died on 1st March 1881 according to the Julian calendar. According to the Gregorian calendar the attack was made 13th March 1881.

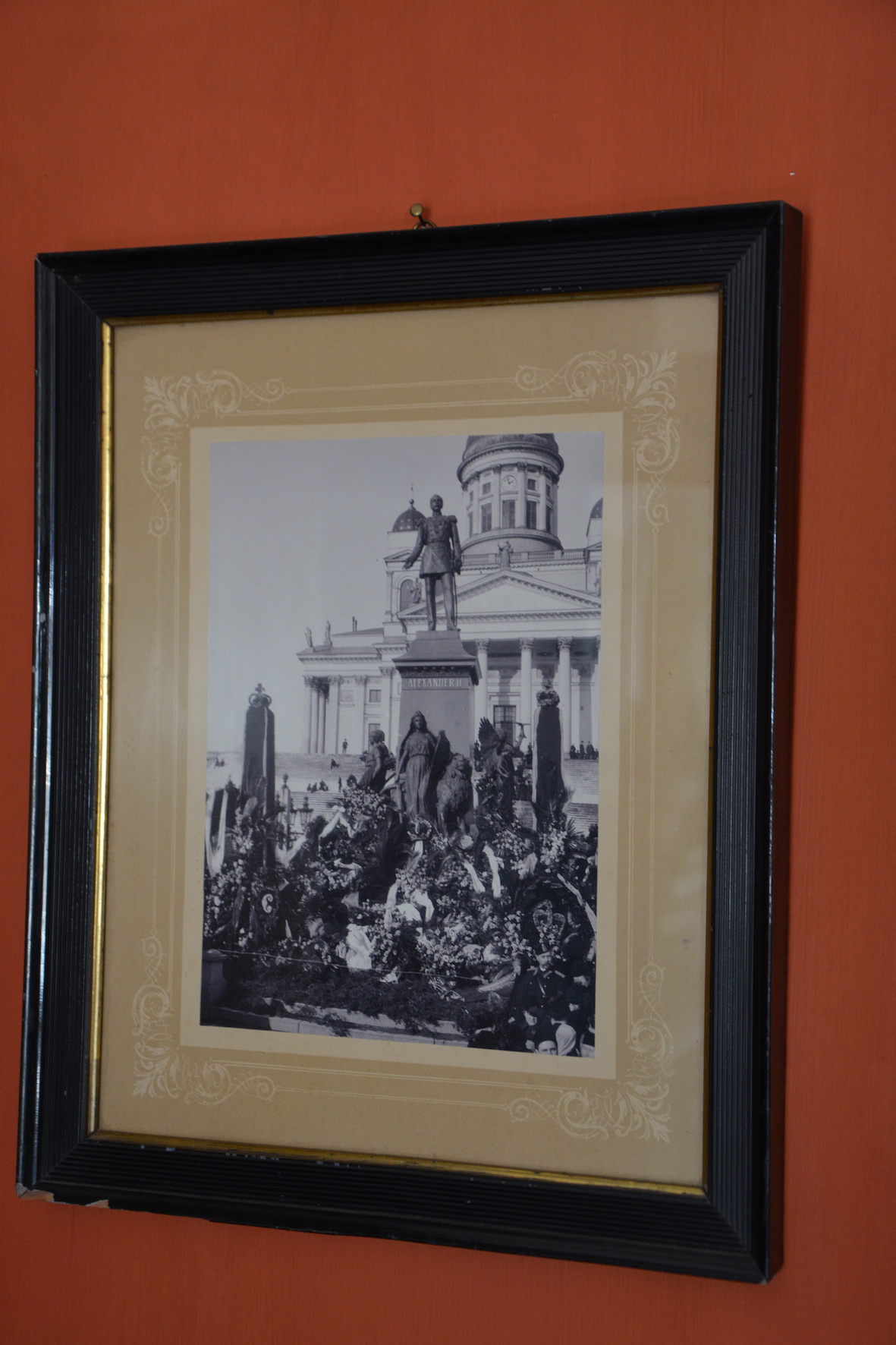

Both in Finland and in Russia the murder of the liberal emperor that had made important reforms caused great grief. The Finns erected a monument in memory of the emperor on the most noble spot in Finland: in the center of the Senate Square in Helsinki. The statue was designed by the artists Johannes Takanen and Walter Runeberg and was ready in 1894.

Ticket for the unveiling of the Alexander II’s monument at the Senate Square in 1894. A patriotic unveiling ceremony was held during a meeting of the assembly of the land. Photo: Helsinki University Museum.

This photo from 13th March 1899 depicts the monument covered in flowers. The flowers were placed here during a memorial commemorating the day of the murder 18 years earlier. The flowers were a Finnish homage to the liberal emperor. Eventually vast changes leading towards an independent democratic system were made by the Finnish society in the beginning of the 20th century.

Photo of the flowers in front of the statue of Alexander II in Helsinki in Marsch 1899. Picture in the exhibition in Hertonäs Manor Museum. SOV.

After the October Revolution in Russia in 1917 many statues of the emperor were removed, but the statues in Sofia in Bulgaria, and in Helsinki remain intact today. The statute was left in its place even after Finland declared independence from Russia on the 6th December 1917 due to the fact that Alexander II still represented a fair and liberal period of regency for the Finns. The photo is on display at the museum in Hertonäs manor in Eastern Helsinki.

Sources:Backman, Sigbritt, Hertonäs gård - från säterier till museum, SOV, Helsingfors 2016.

Engman, Max, Språkfrågan: Finlandssvenskhetens uppkomst 1812–1922, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Bokförlaget Atlantis, Helsingfors och Stockholm 2016.

Klinge, Matti, Finlands historia 3, Schildts, Helsingfors 1996.

Meinander, Henrik, Finlands historia: Linjer – Strukturer – Vändpunkter, rev. upplaga. Schildts & Söderströms, Helsingfors 2014.

Radzinskij, Edvard, Alexander II. Den siste store tsaren, övers. Staffan Skott, Norstedts, Stockholm 2008.

Thylin-Klaus, Jennica, Särdrag, stavning, självbild: En idéhistorisk studie av svensk språkplanering i Finland 1860–1920, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsingfors 2015.

Translation: EAW 2021.